- Home

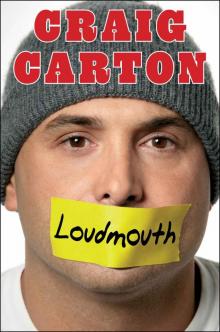

- Craig Carton

Loudmouth: Tales (and Fantasies) of Sports, Sex, and Salvation from Behind the Microphone

Loudmouth: Tales (and Fantasies) of Sports, Sex, and Salvation from Behind the Microphone Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

* * *

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Prologue: Seeing My Shadow

1. Bald, Broken, and #1

2. Vietnam Baby Act

3. The Top’s Better Than the Bottom

4. A Good Dose of Scandal

5. Sexy Jesus

6. Confucius Say: Try Not to Puke on Egg Roll

7. I Hate Sundays

8. The Nose

9. Put a Glove on It

10. Busted

11. Hello, Princeton!

12. School Tripping

13. If She Looks Too Young, She Is

14. No-Hitters

15. A Jackson and a Wink

16. Cockroaches and Old People

17. Radio Rat

18. One Lap Dance Over the Top

19. Room Service, With a Little Extra

20. Revenge of the Pussy Maven

21. Don’t Be That Guy

22. Kardashian, Without the Ass

23. The Good Stuff

24. The Greatest Trade of All

25. Every Vagina in the Free World

26. Girls of Denver

27. Three Little Words

Acknowledgments

Dedications

About Craig Carton

I’m all alone in the back of an SUV. It’s 35 degrees outside, where there are several thousand people all chanting my name, all wanting to see the clown who for the second year in a row is about to walk across the Brooklyn Bridge in little more than a Speedo and a football jersey.

How did I get myself into this position again, and why in the world does it make me so happy?

It’s 10:40 in the morning, and a radio station employee charged with protecting me cracks open the door and asks if I am ready to go. Actually, “ready to do this” are his words.

Not yet.

I take off my sweatpants, revealing my green New York Jets Speedo. Suddenly I have an attack of ego. How’s it look? I wonder. I’m not thinking about my legs; I am worried about whether or not my junk looks okay.

“Craigie, Craigie, Craigie!”

The people are restless and cold, too. They want to start the walk. The crowd includes marching bands, mascots, strippers, and thousands of die-hard Jets fans pumped to celebrate their team making it into the AFC Championship game. Holy shit, it’s only been eighteen months since I started hosting the Boomer & Carton show on WFAN, and now there are thousands of people waiting for me to appear like I’m Phil, the groundhog.

Thankfully I find a pair of ankle socks in my bag and decide to stuff my Speedos with them. It looks so ridiculous, you might think I have hemorrhoids, but I don’t care. So I leave them in there; better this way than reality on this cold day.

I take a few more deep breaths and catch my reflection in the rearview mirror. I freeze. Only one thought, and it’s clear.

This is fucking awesome!!!

I swing the door open wide and let the circus begin. The crowd is everything I had hoped it would be. Brooklyn’s Cadman Plaza overflows with all sorts of people: young kids, old men and women, even some people in their Speedos to support me and the Jets—probably more the Jets than me, but they’re here. Every local news station is on hand, as are two marching bands and the New York City Police Department, in force. The plan is to walk across the entire span of the Brooklyn Bridge, stopping only at the midway point to do a Jets cheer.

The first face I see when I get out of the SUV is my radio partner’s: Boomer Esiason. Boomer was once an NFL MVP for the Cincinnati Bengals, won the Walter Payton Award for Man of the Year, and raised more than $80 million to fight cystic fibrosis. Now he is standing next to his half-naked radio partner and participating in a walk across the bridge with thousands of people whom he would never, under normal circumstances, allow inside his house to use the bathroom. And that’s why I love him, and why our show works. Boomer bought in 100 percent to what I thought we had to do to be successful, to get attention, and to connect with a rabid fan base. This bridge walk trumped the Ickey Shuffle by a long shot.

Boomer was on the phone back to the radio station doing a live segment with the midday show on WFAN with Joe Benigno and Evan Roberts. I’m sure those two guys hated having to go to Boomer live for the walk, and I’m even more sure they hated the whole idea of what we were doing. They are straight sports guys, so anything other than a dialogue about the most recent game was outside of their scope of conversation. Plus, Joe had gone out of his way to be an asshole to us when we first started, so having to give us this kind of attention had to kill him—just as Boomer and Carton becoming the number-one-rated show on the station and in morning drive in New York had to bother him to his core.

When we first got to the station, our show, which was the same as it is today, was so different from anything else WFAN had on the air. We replaced Don Imus, who’d been kicked off the air for his “nappy-headed hos” comment, and as a result of replacing Imus and for no other reason, we were deemed lesser talents than him by our fellow hosts. Joe decided it would be a good idea to go on the highly rated afternoon show and attack me by telling their audience that he didn’t like me or our show.

I was pissed. Why would Joe, or anybody else for that matter, attack the new morning show? We are his lead-in. The better we do, the better chance he has of getting ratings. His attack made no sense to me. I listened to his comments a few times and then decided I would fight back. Joe attacked because he thought he would ingratiate himself to Mike Francesa, the longtime afternoon show host who also, by his own admission, went out of his way to try to prevent us from being successful.

In reality, Mike didn’t give a shit what Joe thought, but he certainly cared about how the station was reacting to us and to this event. So much so that when I called Mike on his behavior years later, he admitted, and I quote: “We were jealous of all the attention you guys were getting.” I was later told that as the WFAN newsroom listened to coverage of my walk, Mike came out of his office looking for the info on a story he wanted to talk about on the air later that day. When he couldn’t get anyone to turn away, he yelled, “Stop paying attention to some idiot walking across a bridge! I need a sound bite now!”

I had been in radio for nearly twenty years at this point and had been through my share of battles. Joe Benigno wasn’t going to attack me on the air and not be told how stupid it was. The next day I started attacking his age, his sound, and his show. He came into the studio where our producer sits, and probably was figuring I would bring him on the air and give him a chance to defend himself, but I gave him no such shot. I waited until we went to a commercial and then called him in.

Before the door could close all the way, I explained in very clear terms how ridiculous and offensive his baseless attack was and that we wouldn’t tolerate it again. Joe left the studio without saying a word.

Five years later, our relationship is more than cordial—although we are not friends—and I firmly believe the Joe and Evan midday radio show is the best midday show the radio station has ever had.

“Craigie is out of the car, and will begin the walk after five strikes of the triangle,” Boomer told the WFAN audience. When I was a high school sophomore, my parents made me join the New Rochelle High School Marc

hing Band. I played the drums, but also at one point I had to play the triangle for a particular song. This fact made great fodder for our show, and I felt it only appropriate to relive those days. So out came the triangle, and five hits later, I was on my way.

There is something surreal about having people watch you walk. I not only became aware of how I walked, I became insecure about it. Do I walk funny? Do I have a cool, confident walk? Do I . . . ugh, stop! My brain was in overload. So I stopped walking, raised my bullhorn above my head, and chanted “J-E-T-S! Jets, Jets, Jets!” Luckily, the thousands of people behind me echoed my chant in broken unison. A simple chant, and I was back on my way. God, do I love Jets fans.

Six-oh-three—nice job, Eddie! Welcome, welcome, welcome! Boomer Esiason and Craig Carton ohhhhhhhhnnnn The Fan, and we have a great show for you today.

The first time I said that line was on September 4, 2007. It was the single most rewarding professional sentence I’ve ever spoken. I have been blessed to say it every day now for five years in a row. Some said I would be an “overnight success”; others said I’d never make it. “What a terrible choice,” the columnists wrote. “The show has no chance,” bloggers predicted. And some listeners complained that I was arrogant and full of myself. I not only remember every negative word written, spoken, and blogged about that first show, I remember every single person who said each thing. I use them and their comments as fuel to drive me to be the best, most successful radio host in the world.

Overnight success, huh?

I was an intern at WFAN Radio twenty-four years ago when they celebrated their first birthday—at a time when most radio experts thought they would never see a second.

“He’ll never make it”—okay, asshole, perhaps you forgot to check my background. I was mentored by the legendary Bob Wolfe, the man who called Don Larsen’s perfect game in the 1956 World Series, when I took a class at Pace University while still enrolled in high school. Maybe you didn’t realize that I was a major ratings success in Buffalo, Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Denver. “What a terrible choice,” they said—but did they know that I was the single most-listened-to afternoon radio host in America, or that I was the host around whom an entire syndication company started, which would be heard in more than forty cities?

I was, and am, confident—but hardly cocky or full of myself. Not when I grew up with parents who never fostered self-confidence, but instead locked me in traction to try to knock the Tourette’s out of me, or kicked me off the varsity sports teams in high school so I could spend more time studying and join the marching band. My parents were so involved in my life that I was guarded more viciously than the gold at Fort Knox.

I laugh at all of it now. All of the skeptics who said I would never amount to anything in radio. I laugh at the way I was raised. I laugh on the outside, and I put on a good show. Life is like day camp to me. That’s my personal mantra, and I try to live up to it as much as I can. But on the inside, I’m still a somewhat insecure child who worries about ratings, about when my show will come to an end, and about not being good enough for my boss, my partner, my wife, and my family.

I can’t believe that I host the most-listened-to morning radio show in all of New York, even though I know I’m good enough to do it. I can’t believe that I replaced Don Imus and, along with my partner Boomer Esiason, have better ratings every month than Imus had in more than twenty years on the radio. Yet I also believe that there was nobody better in America to replace him than me.

Deep down, I am conflicted. I can’t have a basic one-on-one conversation without getting fidgety and uncomfortable, yet I can stand on a stage with a microphone in my hands and perform in front of thousands of people without breaking a sweat or raising my heartbeat. Radio is my salvation; it’s my escape from reality. On air, I can be anyone I want to be, and I have chosen to be a super self-confident, fun-loving guys’ guy. Off the air, I’m an introverted loner who has no problem staying in the house or avoiding interaction with people. Radio is my drug. I need a microphone and an audience, even if I can’t see them, to release my demons—both real and imagined. It’s no wonder I picked the most insecure profession in the world to be my life’s calling.

Sports and radio: what a wonderful combination. As a kid, the field or the court was my salvation, or my release from reality. From sunup to sundown I was outside playing. As an adult, I did what came most naturally, which was to keep sports in my life by talking about them. The more I get to talk about other people, the less I have to focus on myself. I therefore rarely take days off.

For five years now, the Boomer & Carton radio show has been number one in the ratings, and yet I still sweat out my Monday noon phone call with Mark Chernoff, my boss, when he tells me the weekly ratings. I sweat tenths of a point. I get depressed if our lead dwindles by even a fraction of a point, and then celebrate being number one, moments later.

I host the number-one show in radio, and yet my greatest professional satisfaction is being able to tell the naysayers to fuck off. Proving people wrong is a side job for me.

Yet I live every day as if it can all end tomorrow. That being said, when the haters continue to write malicious things about me, one fact cannot be denied: I may be bald and broken, but I made it to the top.

My first and earliest childhood memory is of when I was five years old and attending a Montessori nursery school. Dressed in bad plaids and corduroy, I had to go to the bathroom in the worst way: kidneys ready to explode, legs crossed, hoping to hold back the flow. Meanwhile Joey was in the bathroom and apparently not coming out anytime soon. I held on to a huge wooden block the size of a redwood stump with the bathroom key attached. Finally I couldn’t hold it anymore. I pulled my corduroys down to my ankles and started to pee into the small plant the class was raising in hope of relocating it outside.

You would think the real trouble would begin when the teacher caught me doing it. But since it was the end of the day, she didn’t say a word. Instead, she beckoned to my mother, who was waiting to take me home, and brought her into the classroom. My teacher whispered in her ear and set off a whirlwind of trouble for me that would be a constant throughout my life. My mother grabbed me and asked me what I did.

I didn’t say anything.

“Did you go number one in that plant?” she asked, more a statement than a question. Again I didn’t say anything; already I was exhibiting the traits of a great mob witness. But then I heard the line that still echoes in my ears to this day:

“Wait till your father finds out what you did! You’re in big trouble, mister.”

When I got home, I wasn’t allowed out of my bedroom, as punishment for peeing in the plant. What was I supposed to have done? Wet my pants? Even now, as I look back on it, I think I did the right thing. When my father got home, my mother apprised him of the situation, and he berated me for a while. I don’t remember all the specifics, but I do remember what he said right before he left my room: “You will not embarrass us again!”

Wrong, sir. I was just getting started.

Later that summer, my parents decided to enroll me in a local day camp to get me out of the house. The camp was a few miles from our house, and it was typical in that you got to swim, play some sports or do outdoor activities, and then get picked up. It’s funny how your brain works, because I have only one memory of that time, and it’s got nothing at all to do with the camp itself.

Our neighborhood was filled with kids, and across the street from me lived a kid I will call Frankie Wegurd. Frankie was the only kid I knew who had a Jacuzzi, so we played at his place a lot. Frankie had another thing no one else at the time had, or at least that I knew about: his parents and their best friends swapped spouses.

As the story went, they were swingers who liked to experiment sexually. One night while in that very Jacuzzi, they started fooling around with the opposite spouses. Things heated up, and afterward they got to talking about how they would like to switch partners for a while. As they played out the fantasy, they

also realized that they were better matches with each other’s spouse. They agreed to separate on a temporary basis and give it a whirl. Frankie’s father moved out, and the husband of the other couple moved in. They were divorced and remarried all within a year, and as far as I know, they have stayed that way.

Frankie and I did have one thing in common: we both had dogs. Mine was an old wire-haired terrier that my parents got long before I was born. His name was Tober because he was born in the month of October. One day, Frankie’s dog got out of his backyard and came over to our house to play with Tober. They started to growl at each other, and I went to grab Tober’s chain to pull him away.

In a split second, Frankie’s dog chomped down on my hand. Its teeth punctured my skin below the thumb and scratched my wrist. Frankie yelled louder than anyone I’ve ever heard before. I was kind of stunned. I didn’t yell or cry. I was just in this weird, surreal place, taking it all in. My parents ran outside and saw me bleeding and the dogs barking at each other. They scolded Frankie and his dog, then rushed me to the doctor for a tetanus shot.

It could have been a lot worse, but my parents were furious at Frankie. For a while they forbade him from coming over, because they figured it had to be his fault—as if he had commanded his dog to attack me.

The next day was a camp day, and I remember that I had to decide whether or not I wanted to go, since my hand was bandaged. I’ll never forget my mother making me bacon and eggs and my father sitting me on his lap, wearing his typical white T-shirt and jeans. I also remember that my mother liked to save the oil in the pan after cooking the bacon. She would pour the leftover oil into a mason jar and keep it under the kitchen sink, reusing it to cook other meals, or pouring it onto the dog’s food. That Tober didn’t die of clogged arteries is a minor miracle.

I was gazing out the kitchen window with my brother, waiting for the bus to pick us up, when my father said that he had a rare day off. If I wanted, I could stay home and spend the whole day with him. My father never had a weekday off, and he never wanted to spend his spare time with me. But at this moment life was still good; I hadn’t figured out many of the things I would later realize about my parents. I should have said, “Dad, I’m with you; let’s go have fun.” Instead I said, “No thanks, I want to go to camp.”

Loudmouth: Tales (and Fantasies) of Sports, Sex, and Salvation from Behind the Microphone

Loudmouth: Tales (and Fantasies) of Sports, Sex, and Salvation from Behind the Microphone